China says it has successfully landed a robotic spacecraft on the far side of the Moon, the first ever such attempt and landing.

At 10:26 Beijing time (02:26 GMT), the un-crewed Chang’e-4 probe touched down in the South Pole-Aitken Basin, state media said.

It is carrying instruments to analyse the unexplored region’s geology, as well to conduct biological experiments.

The landing is being seen as a major milestone in space exploration.

There have been numerous missions to the Moon in recent years, but the vast majority have been to orbit, fly by or impact. The last crewed landing was Apollo 17 in 1972.

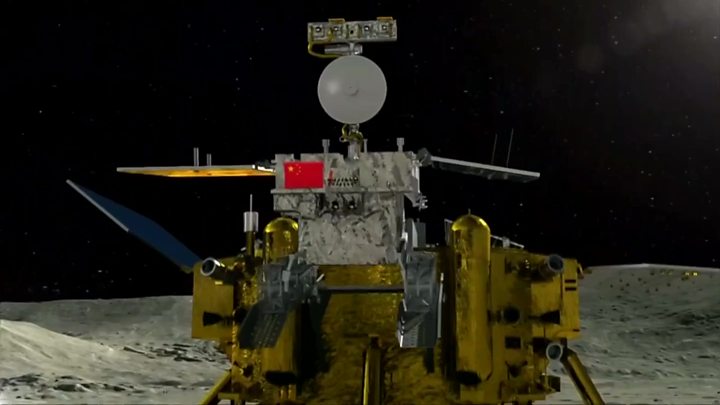

The Chang’e-4 probe has already sent back its first pictures from the surface, which were shared by state media.

With no direct communication link possible, all pictures and data have to be bounced off a separate satellite before being relayed to Earth.

Why is this Moon landing so significant?

Previous Moon missions have landed on the Earth-facing side, but this is the first time any craft has landed on the unexplored and rugged far side.

Ye Quanzhi, an astronomer at Caltech, told the BBC this was the first time China had “attempted something that other space powers have not attempted before”.

The Chang’e-4 was launched from Xichang Satellite Launch Centre in China on 7 December; it arrived in lunar orbit on 12 December.

The Chang’e-4 probe is aiming to explore a place called the Von Kármán crater, located within the much larger South Pole-Aitken (SPA) Basin – thought to have been formed by a giant impact early in the Moon’s history.

“This huge structure is over 2,500km (1,550 miles) in diameter and 13km deep, one of the largest impact craters in the Solar System and the largest, deepest and oldest basin on the Moon,” Andrew Coates, professor of physics at UCL’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory in Surrey, told the BBC.

The event responsible for carving out the SPA basin is thought to have been so powerful, it punched through the Moon’s crust and down into the zone called the mantle. Researchers will want to train the instruments on any mantle rocks exposed by the calamity.

The science team also hopes to study parts of the sheet of melted rock that would have filled the newly formed South Pole-Aitken Basin, allowing them to identify variations in its composition.

A third objective is to study the far side regolith, the broken up rocks and dust that make up the surface, which will help us understand the formation of the Moon.

What else might we learn from this mission?

Chang’e-4’s static lander is carrying two cameras; a German-built radiation experiment called LND; and a spectrometer that will perform low-frequency radio astronomy observations.

Scientists believe the far side could be an excellent place to perform radio astronomy, because it is shielded from the radio noise of Earth. The spectrometer work will aim to test this idea.

The lander carries a 3kg (6.6lb) container with potato and arabidopsis plant seeds – as well as silkworm eggs – to perform biological studies. The “lunar mini biosphere” experiment was designed by 28 Chinese universities.

Other equipment/experiments include:

- A panoramic camera

- A radar to probe beneath the lunar surface

- An imaging spectrometer to identify minerals

- An experiment to examine the interaction of the solar wind (a stream of energised particles from the Sun) with the lunar surface

The mission is part of a larger Chinese programme of lunar exploration. The first and second Chang’e missions were designed to gather data from orbit, while the third and fourth were built for surface operations.

Chang’e-5 and 6 are sample return missions, delivering lunar rock and soil to laboratories on Earth.

Is there a ‘dark side of the Moon’?

The lunar far side is often referred to as the “dark side”, though “dark” in this case means “unseen” rather than “lacking light”. In fact, both the near and far sides of the Moon experience daytime and night-time.

What are China’s plans in space?

China wants to become a leading power in space exploration, alongside the United States and Russia.

In 2017 it announced it was planning to send astronauts to the Moon.

It will also begin building its own space station next year, with the hope it will be operating by 2022.

The BBC’s John Sudworth in Beijing says the propaganda value of China’s leaps forward in its space programme has been tempered by careful media management. There was very little news of the Chang’e 4 landing attempt before the official announcement it had been a success.

But Fred Watson, who promotes Australia’s astronomy endeavours as its astronomer-at-large, says the secrecy could simply be down to caution, similar to that shown by the Soviet Union in the early days of its competition with Nasa.

“The Chinese space agency is a young organisation, but perhaps in years to come, it will catch up,” he told the BBC.

Ye Quanzhi says China has made efforts to be more open.

“They live-streamed the launch of Chang’e 2 and 3, as well as the landing of Chang’e 3. PR skills take time to develop but I think China will get there,” he said.

China has been a late starter when it comes to space exploration. Only in 2003, it sent its first astronaut into orbit, making it the third country to do so, after the Soviet Union and the US.

The far side landing has already been heralded by experts at Nasa as “a first for humanity and an impressive accomplishment”.