Egypt’s streets are turning into a daily forum for airing a range of social discontents from labor conditions to fuel shortages and the casualties of myriad clashes over the past two years.

Parliamentary elections called over the weekend by the Islamist president hold out little hope for plucking the country out of the turmoil. If anything, the race is likely to fuel more unrest and push Egypt closer to economic collapse.

“The street has a life of its own and it has little to do with elections. It is about people wanting to make a living or make ends meet,” said Emad Gad, a prominent analyst and a former lawmaker.

Islamist President Mohammed Morsi called for parliamentary elections to start in late April and be held over four stages ending in June. He was obliged under the constitution to set the date for the vote by Saturday.

“I see that the climate is very agreeable for an election,” Morsi said in a television interview aired early on Monday. He also invited all political forces to a dialogue on Monday to ensure the vote’s “transparency and integrity.”

Morsi’s decree calling for the election brought a sharp reaction from Egypt’s key opposition leader, Nobel Peace Laureate Mohamed ElBaradei, who said they would be a “recipe for disaster” given the polarization of the country and eroding state authority.

On Saturday, ElBaradei dropped a bombshell when he called for a boycott of the vote. An effective boycott by the opposition or widespread fraud would call the election’s legitimacy into question.

But in all likelihood, Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood and its ultraconservative Salafi allies will fare well in the vote. The Brotherhood has dominated every election in the two years since the 2011 uprising that ousted autocrat Hosni Mubarak.

The mostly secular and liberal opposition will likely trail as they did in the last election for parliament’s lawmaking, lower house in late 2011 and early 2012 — a pattern consistent with every nationwide election post-Mubarak.

President Morsi’s Brotherhood-dominated administration has been unable to curb the street protests, strikes and crime that have defined Egypt in the two years since the uprising.

In fact, the unrest has only grown more intense, more effective and has spread around the country in the nearly eight months that Morsi has been in office.

On any given day, a diverse variety of protesters across much of the troubled nation press demands of all sorts or voice opposition to Morsi and the Brotherhood.

Sunday was a case in point.

Thousands of brick workers blocked railroad tracks from a city south of Cairo for a second successive day to protest rising prices of industrial fuel oil, crippling transportation around the country of 85 million.

The rise resulted from the government’s decision last week to lift subsidies on some fuel prices. It is part of a reform program aimed at securing a $4.8 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund.

Meanwhile there are ample signs that Egypt’s economy is deteriorating steadily.

Foreign reserves have dropped by nearly two thirds since Mubarak’s departure, the key tourism sector is in a deep slump and the local currency has fallen nearly 10 percent against the dollar in the last two months.

Khaled el-Hawari, a marketing executive in one of the brick factories, said industrial fuel oil prices increased by 50 percent, threatening the business and the livelihoods of hundreds of workers who could be laid off.

“No one is listening to us or responding,” he said. “We plan to protest outside the Cabinet next.”

In the Nile Delta province of Kafr el-Sheikh, hundreds of quarry workers stormed the local government building, forcing staff to flee. The workers are demanding permanent employment in the factory. They chanted against the recently appointed local governor, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood.

In the coastal city of Port Said, a general strike entered its second week on Sunday. The city has practically come to a halt as thousands of workers from the main industrial area joined the strike.

When asked about the strike in Port Said, Morsi suggested that the unrest there was primarily the work of “outlaws” and “thugs” who intimidated residents to take part in the general strike. He vowed to deal decisively with them in Port Said and elsewhere in the country.

“There is no place for thugs or those who resort to violence,” Morsi said in the interview, recorded on Sunday but aired Monday 5 ½ hours behind schedule.

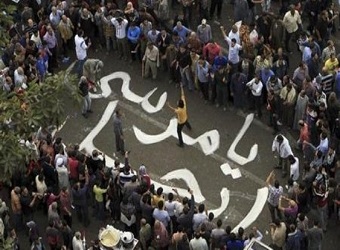

Calls for a civil strike in line with the one in Port Said have spread around Egypt. A group of protesters blocked the entrance to a major administrative building in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, stopping citizens from entering and prompting small scuffles.

But Port Said is emerging as a prime example of how the popular discontent is evolving into sustained anti-government action. There are even calls in Port Said for secession which, while not realistic, indicate the depth of anger.

Activists there are demanding retribution for more than 40 residents killed there last month, allegedly by police.

The killings took place amid a wave of anger that swept the city after a Cairo court passed death sentences against 21 people, mostly from Port Said, for their part in Egypt’s worst soccer disaster on Feb. 1 2012. Morsi said in the interview that he has ordered an investigation into the killings and that he planned a visit to Port Said but did not say when.

Morsi’s supporters say that delaying elections, protesting and boycotting are affecting Egypt’s ability to lure foreign investors and tourists again as the economy deteriorates.

Lack of confidence in law enforcement has reached a point where villagers sometimes hunt down alleged killers, lynch them and burn their bodies with police unable or unwilling to intervene.

With violent crime on the rise, rights groups accuse police under Morsi of falling back to the brutal methods and impunity of the Mubarak days.

The opposition, which led the uprising against Mubarak, is showing signs of disarray.

Another emphatic Islamist victory, especially if enough opposition groups do not heed ElBardei’s boycott call, is likely to deal a body blow to the National Salvation Front — the main opposition coalition.

In short, there is no end in sight to the growing popular discontent with Morsi’s rule and the Brotherhood, who are accused by opponents of monopolizing power.

Already, ElBaradei’s call for a boycott has sown divisions with his movement, with some of its leading figures saying the former director of the U.N. nuclear agency spoke prematurely and without sufficient consultation with other leaders. Others said they would heed the boycott call.

Ahmed Maher, the leader of the opposition April 6 youth group, said if the entire opposition does not join the boycott, it would be a “gift” to the Brotherhood and would accord legitimacy to a Brotherhood-dominated parliament. A successful boycott, he added in a statement, must be accompanied with a “parallel” parliament and a shadow government for it to be effective.

Significantly, some activists say that with international monitoring of the upcoming elections to prevent widespread fraud, the Brotherhood and their Salafi allies may not get the comfortable win they are hoping for.

“Entire cities and provinces have turned against the Brotherhood,” said activist Ahmed Badawi. “This is a good time to defeat the Brotherhood because the economic crisis is hurting people’s lives and they are angry.”

But Gad, the former lawmaker, pointed out that staggering the elections over a two-month period would only benefit the Brotherhood, which had gained valuable election expertise when it had for years under Mubarak fielded candidates in parliamentary elections as independents.

“They have their election pros who will now be put to work in all four stages to ensure their supporters go out and vote while orchestrating soft fraud which, if widespread, can alter the results,” said Gad.

The Brotherhood has been repeatedly accused of influencing voters at polling centers, campaigning on voting day in violation of the law and taking advantage of the relatively high percentage of illiteracy among voters. Some also accuse the Brotherhood of buying votes, exploiting the country’s widespread poverty.

The Brotherhood denies the charges and counters them by boasting of its superior organizational skills. The group said it has the legitimacy of its consistent victories at the ballot box and accuses its opponent of trying to overthrow a democratically elected government.

In the interview with the private Mehwar television, Morsi also tried to improve his standing nearly eight months into his four-year term.

He repeatedly declared that he was a “president for all Egyptians,” claimed he had no quarrel with any of the nation’s political forces and reasserted his respect and confidence in the powerful military, which has recently shown signs of impatience with Morsi’s rule.

He vowed to continue his four-year term and, in an emotional bid to win public sympathy, said: “I hope that my fellow Egyptians will forgive me if they see me making a mistake.”

He added: “We are together walking a path that is covered with thorns, but our feet are thick and we will complete the journey together even though our feet are bloody.”

Associated Press