Shell’s exit from the onshore oil sector in Nigeria puts the spotlight on the risks oil business face in the country but has sparked hopes that local companies could take over to prevent the Niger Delta’s output decline, as per a Reuters report citing industry officials and analysts.

Shell’s decision to leave the Delta came in light of the many issues the region faces such as pollution, oil theft and pipeline vandalism. For years, those problems have hindered investment, production, and government finances. It’s noteworthy that Shell was a pioneer in Nigeria’s oil sector.

The company’s decision to sell its subsidiary to five primarily local businesses is in line with a growing pattern of Western energy companies selling their onshore oil fields in Nigeria. In recent years, Exxon, Eni of Italy, Equinor of Norway, and Addax of China have all reached agreements to sell assets in the country.

“Nigeria has had well-established problems in policy in the oil sector, and the FX policy concerns have put constraints on investments. That’s probably partially why you have seen the majors pulling out, and disinvesting to some extent,” Andrew Matheny, senior economist with Goldman Sachs said.

“It explains a significant portion of the decline in oil production in recent years.”

When President Bola Tinubu took office in May of last year, he committed to removing barriers that producers faced, such as preventing pipeline vandalism and theft of crude. However, the asset sales—which were well underway before his election—highlight the nation’s oil sector’s inevitable changes seven months into his presidency.

“If companies are now leaving the less capital-intensive onshore operations to focus on offshore operations, it sends a perfect picture of the risk involved in doing business in Nigeria,” Seyi Awojulugbe, a senior analyst at security consultancy SBM Intelligence in Lagos told Reuters.

Spills, Money, and Emerging Local Businesses

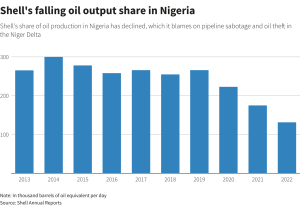

In Nigeria, Shell produced up to 300,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day (boed) ten years ago. According to the company’s annual reports, this dropped to 131,000 boed in 2022, which it attributed to theft and sabotage in the Niger Delta.

According to industry analysts, the majors hoping to divest, like Shell and Exxon, were not investing much in developing onshore assets, which was speeding up the decline in production.

“For many years, the majors decreased their investments in the onshore sector,” stated Roger Brown, CEO of Seplat Energy in Nigeria. He mentioned the mix of regional problems and the fact that big oil companies must compete for money with their holdings in other, sometimes more appealing, places like Guyana.

“I think the independent companies will get production up more than the IOCs will because they do have the appetite to invest,” Brown added.

Seplat’s, a local firm, agreement to acquire Exxon’s onshore assets was announced in February 2022, but it has not yet received regulatory approval. The junior oil minister of Nigeria stated that local businesses would be able to fill the void left by Shell’s asset sale and that the sale would be approved promptly upon receipt of all necessary documentation.

Seplat, First E&P, and Heritage are a few local businesses that have been successful in increasing production and decreasing oil spills on assets they bought from Shell.

For some, however, like Aiteo Eastern E&P and Eroton Exploration, who have battled with leaking pipelines and oil spills, it hasn’t worked.

According to Richard Bronze, head of geopolitics at London-based Energy Aspects, the lack of financial clout of oil majors in local firms could have an impact on future output.

However, Brown stated that the oil majors’ access to less expensive capital is meaningless if they are not making investments. Local businesses can also get funding from oil traders, local banks, and certain foreign lenders.

“It will be available but it won’t be cheap,” he said. “But at these oil prices, indigenous businesses can afford to develop it.”