The Yad Vashem Holocaust museum has named an Egyptian doctor to its list of Righteous Among the Nations – the first Arab to be so honored for rescuing Jews during the Holocaust. Mohamed Helmy and a German friend, Frieda Szturmann, saved a Jewish family when the deportations of Berlin’s Jews began in 1941.

Helmy spoke out against government policies and risked his life to save his friends even though he himself as an Egyptian was discriminated against by the Nazis.

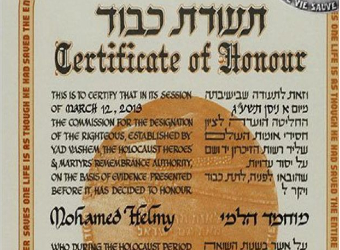

Yad Vashem is now looking for relatives of Helmy and Szturmann to bestow on them the certificates and medals that go with the award. Nearly 25,000 people from 44 countries have been honored as Righteous Among the Nations, including more than 500 Germans and a few dozen non-Arab Muslims.

Helmy was born in Khartoum in 1901, when Sudan was under Egyptian and British administration. In 1922, Helmy moved to Germany to study medicine and settled in Berlin. After completing his studies, he went to work at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin but was dismissed in 1937. A 2009 study by the institute showed that it was heavily involved in Nazi medical policy.

Under Nazi racial theory, Helmy was a Hamit or Hamitic (the descendants of Ham, the son of Noah) – a term adopted in the 19th century and used to define the natives of North Africa including ancient Egyptians and people from the Horn of Africa and southern Arabia. Not being a so-called Aryan, Helmy was forbidden to work in the public health system and was not allowed to marry his German fiancée. In 1939 he was arrested with other Egyptians but released a year later due to health problems.

When the deportations of the Jews from Berlin began, a family friend, 21-year-old Anna Boros (Gutman after the war), needed a hiding place. Helmy brought her to a cabin he owned in the Berlin neighborhood of Buch -it became her safe haven until the end of the war. Whenever he was under police investigation, Helmy would arrange for her to hide elsewhere.

“A good friend of our family, Dr. Helmy … hid me in his cabin in Berlin-Buch from 10 March until the end of the war. As of 1942, I no longer had any contact with the outside world. The Gestapo knew that Dr. Helmy was our family physician, and they knew that he owned a cabin in Berlin-Buch,” Gutman wrote after the war.

“He managed to evade all their interrogations. In such cases he would bring me to friends where I would stay for several days, introducing me as his cousin from Dresden. When the danger would pass, I would return to his cabin …. Dr. Helmy did everything for me out of the generosity of his heart and I will be grateful to him for eternity.”

Helmy also helped Gutman’s mother Julie, stepfather Georg Wehr and grandmother Cecilie Rudnik. Providing for them and attending to their medical needs, he arranged for Rudnik to be hidden in Szturmann’s home. For over a year, Szturmann hid the elderly lady and shared her food rations with her.

But the family was caught in 1944; during their brutal interrogation they revealed that Helmy was helping both them and Gutman. Helmy immediately brought Gutman to Szturmann’s home; only his keen resourcefulness kept him out of trouble.

After the war, the four family members emigrated to the United States but did not forget their rescuers; in the 1950s and early ‘60s they wrote letters to the Berlin Senate lauding them. These letters were uncovered in the Berlin archives and were recently submitted to Yad Vashem.

Helmy remained in Berlin and was finally able to marry his fiancée. He died in 1982; Szturmann died in 1962.

Until the next of kin are identified, Helmy’s certificate and medal will be on display in the Yad Vashem exibition entitled “I am My Brother’s Keeper: Marking 50 Years of Honoring Righteous Among the Nations.”

Source: Haaretz