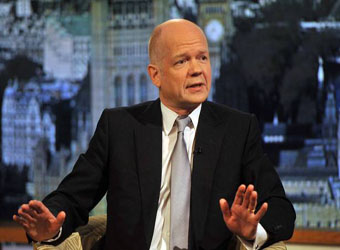

I want to be fair to Mr Hague. He is Britain’s cleverest and most hard-working foreign secretary since Robin Cook. He is the master of his brief. Unlike his dreadful predecessors, David Miliband and Margaret Beckett, William Hague recognises the weight of the Foreign Office as an institution.

He has by far the grandest office in Whitehall (much more so even than the Prime Minister), with a fine outlook over Horse Guards Parade, from where Lord Grey made his famous remark 99 years ago about the lamps going out all over Europe.

Unfortunately, a modern foreign secretary is virtually powerless. The important decisions are made by the prime minister who, in turn, is told what to do by the White House. Mr Hague (or whoever is foreign secretary at any given moment) is thus two degrees away from power.

I am trying to get at the fact that Mr Hague has not been a particularly brave foreign secretary. Neither he nor the Prime Minister has shown the faintest inclination to challenge the fundamental parameters of foreign policy, as set in stone by Tony Blair. Britain will do nothing whatsoever to offend, or even to annoy, the United States. In return, we get to exert “influence” and keep our seat on the security council, where we are valued in the sense that (and only in the sense that) we can be relied upon to vote with the US.

Here’s the deal. We get to retain an illusion of importance. Exactly how much of an illusion can be determined from the fact that it has just taken President Obama eight months to fill the post of US ambassador to London. In return, we do whatever America wants.

This brings me to Mr Hague’s unfortunate performance under questioning from John Humphrys about recent events in Egypt on the Today programme last Thursday. Mr Hague did not merely let himself down. He damaged the reputation of Britain.

The reason Mr Hague was unable to cope is revealing. The United States has not publicly adopted a position about the removal of President Morsi, and we, therefore, have nothing to say either. Britain has to wait until the United States has decided. Mainly thanks to what I believe to be a bitter ongoing argument between the CIA and the state department (but also because of President Obama’s habitual procrastination) this has not happened.

Until the US gives its assent, Mr Hague dare not even define the military takeover as a coup d’état. This American paralysis on the subject is down to an obscure piece of legislation, the Foreign Assistance Act. This stipulates that US aid shall not be awarded “to any country whose duly elected head of government is deposed by a military coup or decree”.

Since the United States wants to go on funding the Egyptian government in the wake of President Morsi’s departure (if their past response to military coups is any guide, aid is likely to go up rather than down following the removal of a democratic government) it is important that no public reference is made to any military coup. Like a fart in the drawing room, it is impolite to mention it.

The omerta does not merely apply in the United States. It is apparently necessary that it should be observed in Britain as well.

So there we are. It is easy to imagine the righteous outrage and horror Mr Hague, a famous eurosceptic, would have felt if the Foreign Office had told him he could not voice his thoughts about Syria owing to a stray Brussels directive. But Mr Hague does not seem to mind that our allegiance with the United States forbids a British foreign secretary from telling the truth about Egypt.

It is important not to be too unkind to Mr Hague. One can imagine all that advice he must be getting: only the military can keep open the Suez Canal, restore order, maintain stability, and guard the border with Israel. Nothing can be achieved without the United States, the Brotherhood can’t be trusted, and, anyway, President Morsi was too close to Iran.

And I have no doubt that Mr Hague is a patriotic man who, after some agonising, has done what he hopes was the right thing. I also suspect that somewhere inside him he knows that he has betrayed every British virtue worth preserving.

Mohammed Morsi is in custody today, yet the only crime he has committed was being elected president of his country. Morsi made mistakes. But he was elected, by a majority of the voters, in free and fair elections. During 12 months in power, he did not – to the best of my knowledge – order the arrest of a single political opponent, of a single dissident journalist, or close down a single newspaper or TV channel.

That has changed now that General al-Sisi’s junta has taken charge. Already, 10 TV channels have been closed down, numerous journalists have been rounded up and taken to jail, and politicians are locked up in a regime of terror; furthermore, a shoot-to-kill policy has been put in place against protesters.

We can understand Mr Hague’s reluctance to upset the United States, which must have given (at the least) a silent blessing to the coup. But it is important to stress that the reluctance of Britain to fill the vacuum left by the moral collapse of Obama’s America carries a significant cost.

Last week’s coup d’état was a crucial counter-revolutionary moment, plotted and paid for by the Arab gulf states. Saudi Arabia has emerged as the leader of a group of repressive and anti-democratic regimes that are determined to shape events in the Middle East as they will.

The well-informed Israeli website DEBKA noted: “The Egyptian military high command was not working alone when its operations headquarters put together the July 3 takeover of power from the Muslim Brotherhood: it was coordinated closely down to the last detail with the palaces of the Saudi and UAE rulers and the operations rooms of their intelligence services.”

Whether deliberately or not, William Hague’s lacklustre response has made him an accessory to this conspiracy. To be fair (once again) to the Foreign Secretary, he is not alone. Douglas Alexander, shadow foreign secretary, has used exactly the same woeful language as Mr Hague. I rang Mr Alexander’s office yesterday and asked three times whether he believed that what had taken place was a coup d’état. But it emerged that the shadow foreign secretary, like the Foreign Secretary, was constrained by the requirements of the US Foreign Assistance Act. Mr Alexander’s spokesman was unable to give an answer.

How easy we find it, ever since 9/11, to abandon our values! President Morsi had been due to visit Britain today. He was booked to meet David Cameron as an honoured guest in Downing Street. What has changed since the meeting was arranged? Only that he has been arrested, and we are collaborating with his captors.

Britain may not be a great power in the world any more, and we can all come to terms with that. But William Hague (and Douglas Alexander, and the Prime Minister) must remember that our relative global impotence should not mean that our magnificent values are no longer of any account.

About the Writer:

Peter Oborne is the chief political commentator of the Daily Telegraph and reports for Channel 4’sDispatches and Unreported World. He has written a number of books identifying the power structures that lurk behind political discourse, including The Triumph of the Political Class. He is a regular on BBC programmes Any Questions and Question Time and often presents Week in Westminster. He was voted Columnist of the Year at the Press Awards in 2013.

Source: The Telegraph