The return of Sudan’s ambassador to Egypt on Monday after a two-month absence is being hailed as an opportunity to ease the strains that have come to characterise relations between Cairo and Khartoum.

“Relations between our peoples and our countries are of historic importance and maintaining them is a duty. Setting them on the right path is our responsibility,” Sudanese Foreign Minister Ibrahim Al-Ghandour told the media earlier this week.

“It is definitely a step in the right direction. It demonstrates Khartoum’s willingness to maintain special relations,” said a diplomat speaking on condition of anonymity.

He warned, however, that the reasons Khartoum withdrew its ambassador in the first place still need to be addressed.

The border issue of Halayeb and Shalatin is one major cause of strain between the two countries.

According to Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukri, Cairo was notified that the Sudanese ambassador’s withdrawal was a result of disputes over the territory. Within days of withdrawing its ambassador, Khartoum renewed a complaint to the UN Security Council demanding Cairo hand over control of the Halayeb Triangle.

Al-Ghandour was quoted by the media last month saying that Egypt and Sudan had agreed not to escalate the dispute.

The Halayeb Triangle is a border area the ownership of which has been disputed since the late 19th century. In 1899, when Egypt and Sudan were under British occupation the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement set the political boundary between the territories at the 22nd parallel, placing the Halayeb Triangle inside Egypt.

Halayeb was not the only point of contention between the two states. In December Sudan accused Egypt and the UAE of deploying troops and military equipment at an Eritrean military base. Troops from Sudan’s rapid response army units sealed the border in response. Neither Egypt nor Eritrea has commented on the accusations. Sudanese troops remain in position and the border with Eritrea is still closed.

Neither Egypt nor Eritrea has commented on the accusations. Sudanese troops remain in position and the border with Eritrea is still closed.

But it is the Renaissance Dam, an issue last month’s resignation of the Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn has further complicated, that is probably the most difficult outstanding problem between the two capitals.

Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia have yet to agree on water share and the operating process once the dam is operational.

Recent meetings among leaders of the three states have filed to find a solution.

Following a meeting on the sidelines of January’s African Union (AU) Summit in Addis Ababa President Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi said: “People should be reassured. None of the three countries — Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia — will be harmed.”

“There is no crisis between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia. The interests of the three states are as one.”

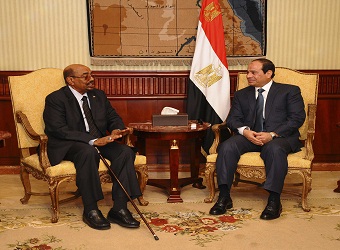

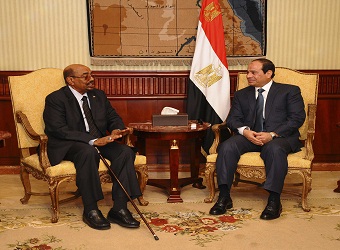

Al-Sisi, Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir and Desalegn agreed to resolve all pending technical issues within a month.

Now Desalegn’s resignation has thrown that optimistic timetable into disarray.

Another second meeting was held between Al-Sisi and Al-Bashir in Addis Ababa on the sidelines of the same summit while a third meeting was convened in Cairo between Al-Sisi and Desalegn during the latter’s visit to Egypt in January.

“Holding all these meeting is supposed to open channels of dialogue and patch up any differences. But nothing has been achieved on the ground,” says the diplomat.

An exchange of accusations has exacerbated the strains. Cairo accuses Sudan of harbouring members of the Muslim Brotherhood while Sudan has accused Egypt of supporting rebels in Darfur. Both countries deny the claims.

Sudan and Egypt also differ over regional issues, not least the dispute between Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain and Egypt on the one hand and Qatar on the other. Khartoum appears to be supporting Doha.

In addition, Egypt remains concerned about the ramifications of Sudan’s decision to lease the Red Sea island port of Suakin to Turkey.

Announced in December, the decision exacerbated tensions between Cairo and Khartoum. There was widespread speculation Turkey was seeking to establish a naval base on the island.

In Egypt the media portrayed the move as a threat to national security.

Speaking to reporters following a meeting with Al-Ghandour in January, Shoukri called on the Egyptian and Sudanese media to be objective and not to insult the peoples or leaders of the two countries. Al-Ghandour said the Egyptian and Sudanese media must “observe the sanctity of relations” in the future.

A meeting between Shoukri, Al-Ghandour, and the heads of both countries’ intelligence agencies was held last month, offering an opportunity to open channels of dialogue and narrow any outstanding differences.

It resulted in a joint statement in which Cairo and Khartoum agreed to work towards enhancing security and military cooperation and establish a mechanism for political and security consultation.

The statement also outlined preparations for a meeting of a joint committee, chaired by the presidents of Egypt and Sudan, in Khartoum. The last time the committee met was in Cairo in 2016.

The statement also underlined the importance of coordination between the two states over Nile water management within the framework of their commitment to agreements already signed between them, including the 1959 Nile Water Agreement.

The 1959 accord guarantees Egypt 55.5 billion cubic metres of Nile water annually and Sudan 18.5 billion cubic metres, quotas Ethiopia refuses to recognise.

Source: Ahram online